16.3

2016: Issue 3: Editorial: Miscellanea

Here we stand at the top of Issue # 3. Sensible Perth will probably be released once every month from here on out – each month’s issue arriving half way through the following month. This is the first issue without an explicit theme, and although we cannot rule out thematic content for future issues, many will surely resemble this one, with its eclectic accumulation of criticism from a particular moment in art. We hope you find something in it anyway.

We are also at the gates of being able to commission writing on a regular basis, and we thank our subscribers for allowing this to happen. We are on the path to providing more thorough and eventually more diverse criticism to the people of our little city. So thank you, and if you have not yet, do consider subscribing. If you also have something to say, then get in touch, either by facebook or our email (sensibleperth(at)gmail.com), and say it! If you want to write something, want to whinge about something, or send a letter to the editor, feel free.

2016: Issue 3: Radical Ecologies: PICA

Radical Ecologies is an unfortunately titled show, and there is a critical response to be had of the premise and artworks in relation to this ostensible thematic. Beyond this, however, there are a number of works that are impressive on their own terms and despite their place in the show.

The problems with the branding and apparent thematic of the show can be drawn back, I would suggest, to Nicholas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics. Although the text is extensively critiqued for its proclivity to overly optimistic politics, it does have at its heart a wonderful definition of the form of the important French art of the 1990s: that relational ‘form’ emerged as a movement away from ‘material form’ and its spreading out into the whole scene as opposed to the isolated object. The end of Relational aesthetics, though, is what interests me. There, Bourriaud brings up Felix Guattari’s Three Ecologies as a potential directive of how to rethink our relationship to art and the world. It is based in Guattari’s proposal to develop an ‘ecosophy’ between three ecological spheres: the subjective, the inter-personal and the environmental. Guattari suggested it was only by realising a nascent subjectivity, a constantly mutating socius and re-inventing the environment that we could avert environmental catastrophe. (As we watch from the other side of dark clouds that already seem to be filling the horizon that separated Guattari from our own time, this seems imbued with a similar unwarranted optimism that has come to define Bourriaud’s position…) Relational Aesthetics seems intended, being framed in this way, to be an argument for the art of the ‘interpersonal’ part of this formula. Even though the text is politically optimistic, it is not simple, nor inappropriate, and turned out to be very, very timely. Principally, it is the definition of the form of Bourriaud’s example works that seem necessary to bring up: their extension out of their material form. It was this movement that led to artworks that take inter-subjective relations as their subject and form, and for artworks that did this to be named the quintessence of relational artistic practice. It is also where the relationship to an ecosophy begins to take shape–the extension of form enabled a reconsideration of our social relations, and beyond this, our environment and subjectivities. The definition of ecology being situated in the relations between things, this makes sense. It is also what is arguably the most ‘radical’ part of Bourriaud’s text: the consideration of art beyond a material outcome, and this as a form of resistance. As Phillipe Parreno, one of Bourriaud’s exemplary relational artists states: ‘it’s exciting when the content overflows the form or the other way round. It’s the irresolution that is interesting. The dynamic of fluids is interesting because they question equilibrium…Is an object always the end of something? does everything really always start with a scenario and end with an object? Should there always be a happy ending to everything?’

Leading on from this, there is a fairly simple criticism I want to direct at this show: why call it what it is clearly not? Especially living as we are in the shadow of Relational Aesthetics, which has as its conclusion precisely the consideration of something that may as well be termed a “radical ecology”. This is not to suggest that objects, sculpture or video cannot be radical, and although no claim can really be made that a certain form is more radical than any other, a contrary demand must be made about why the possibility of something radical being made in a form outside of these discreet things is not present in this show. The second consideration of why there is nothing radical within the discreet objects and videos must also be thought through.

Having said this, there is one work that is a clear exemplary stand out, and that provides an interesting counterpoint to the otherwise object-oriented or discreet video works in the show, and that is Mike Bianco’s bed of bees. It is the only work that seeks out this legacy, this extension of the work outside the isolated object. His painting is also (strangely enough) part of this dynamic – mostly by being seemingly unintended for human view, standing so far above the groundas to be inconvenient to view. Apart from his strange woodcut (that was odd, but charmingly beguiling) his work is the most clearly interested in moving out of being a discreet object or video result and into the relationship between things, including the gallery, the viewer, and living organisms.

It is worth here also mentioning Laetitia Wilson’s response to the show in ArtLink. Her position is well stated, however I would challenge some of the results of her analysis–particularly in relation to Bianco’s work. She also argues that: ‘It could, for instance, have included more actual “life” in the gallery, as ambitiously pursued by Perth-based SymbioticA, who are world pioneers in embracing biological arts.’ While this argument is parallel to my own position regarding the lack of any radical extension of the form of the works away from their material, symbioticA is a bad choice of contrast. Even if they maintain the label of ‘ambitious’, we must admit their final works are as obvious and predictable as the controls they are allowed to perform them in. Their work suffers the same problem as that of Stelarc’s in this show, and who was part of their DeMonstrable show at Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery. His work here is theatrically powerful at least, yet the recorded live feed from London and New York and the audience controlled activity of his arm are entirely arbitrary and pre-determined, and become rapidly uninteresting. This would not be a problem if the subject of the work were not the possibility of this very interactivity (Bianco’s bed is equally predictable, yet also is always alive, always away, providing an ecosystem beyond the gallery, for creatures other than ourselves). There is no puzzle, or anything unpredictable here. It is, like much of the work that SymbioticA undertakes (though Stelarc is not directly affiliated with them), illustration–just with a living performer. It conversely seems inappropriate of Wilson to critique Bianco’s work, as the only work that does include some actual investment in entering into a biological reality, and extending itself away from its discreet object hood, or discreet ‘performativity’ in Stelarc’s case. Wilson claims that it is only putting us in ‘proximity’ as opposed to ‘intimacy’ with bees and that ‘proximity is one step towards intimacy’. Though it is definitely the case that the bee bed is not the positive nor mutual/intimate experience it is probably intended to be, the work is incredibly strong. Though I agree it does nothing to the line of radicalising intimacy with bees, it is one of the works most worthy of sustained critical engagement. It’s dedication to not ending up as an object, but rather something in the process of living, and exuding warmth and smell, makes it one of the few works with a direct investment in the world outside the gallery, and an experience that is not necessarily pleasurable, nor wholly directed towards us, or even our eyes.

I would contrast the work, and indeed the show, unfavourably with someone who is a master of ecological undertakings: Pierre Huyghe’s own work with bees – Untilled (Liegender Frauenakt) [Reclining Female Nude], 2012, features a statue whose head is covered with them. The bees in this statue, originally found in a compost heap outside Documenta 13 are a strange combination of the living, the imagistic, and the inorganic – their open hive is also perceptibly dangerous. Along with the whole cavort of performative, living, active, and unprogrammed things that exist in his work, the bees were a testament to his dedication to a very radical rethinking of the exhibition and the viewer within it, and our own relationship to the environment. However, in this show, Bianco’s work feels like one of the few with a real engagement with what it might mean to be in any way radical, and rethink our relationship to the exhibition, and the bees that fertilise our world.

There are a few works that are very impressive in this show. Katie West’s Decolonist Flag, presented earlier this year at Perth Centre for Photography, is displayed here again. This time, with headphones, the meditative aspects of the work became more pronounced, the breathing of the narrator and their words took on a new importance. This iteration has allowed the work to shine. It is a wonderful piece–even more wonderful for the sense of peace that suffuses it. Rebecca Orchard’s drawings are worthy of attention as well, their delicate, pulsing surfaces among the most accomplished objects in the exhibition. While a simple optical effect, their intensity and interest was not diminished. Peter and Molly’s video works were technically and aesthetically impressive – the most interesting of their series of works featured leeches sucking the artist’s blood. The self-sacrificial and self-harming subtext was powerful and confronting – the inclusion of text was also a welcome addition to the work. However, beside this, the octopi-headdresses appeared somewhat ridiculous, the line from idea to execution being somewhere broken, and the comedy of the situation going unacknowledged. While impressive, there is an absence of self-reflection evident. Nathan Beard’s work was an interesting (though again, not particularly radical nor ecological) work. Here there is a strange relationship being developed: Four Buddha heads in the colonial-oriented British museum, collected from Thailand, though of unclear provenance, are re-created and then slip-cast and glazed with a variety of patterns, also taken from the British museum. The fact that objects, recreated from a colonial museum, are then re-presented in a western gallery context as objects to be bought and sold is a curious interpolation of a dynamic. It seems to be a co-opting of the regimes of a colonial nation. The fact that Thailand was never colonised also puts an ambiguous tilt on the work. The statues have the soft, rounded features of slip cast pottery, revealing the process of their creation. Like all industrial pottery-work, they suffer a loss of definition. However, the creation of slip-cast porcelain models in China, although drawing on a history of the industrial production of kitsch in nations with cheap labour, appears to capitulate to a system rather than co-opt it. The photographs from the British museum are the stronger part of the work for this – they are simultaneously simpler and also more evocative and poetic in their re-casting of colonial enterprise.

The principle reason the show is not as successful as it could be, is not because almost everything there existed to end up in an object, but because it seems to be constantly suggesting at something beyond discreet outcomes, but never going there. There are some amazing objects and videos in this show, that are very interesting artworks. However, it is the misnomer of the ‘radical’ and perhaps even ‘ecologies’ within the title and the framing of the work that does seem at odds with a critical understanding of what is happening within the actual artwork.

By Graham Mathwin

2016: Issue 3: Alex Maciver: New Works

Landscape. 2016. Alex Maciver. Photo: Buratti Fine Art

Alex Maciver has become infamous since his arrival in Perth for turning a wry eye on the city’s cultural lag. Geography does matter in art: particularly social and cultural geographies. Generally, the further you go from major cities, the more conservative art becomes. There is a reasonably large body of contemporary art made in Perth, but this is rarely seen outside of the centre of the city. In a parallel operation, there is a whole gamut of art created in the major cultural powerhouses of other, more cosmopolitan cities, where contemporary art’s value and audience contribute to its development, that we never see here, except online. There is a tinge of conservatism to much that is made here, along with an unwillingness to offend or displease. It is pervasive – even in the contemporary art world. Maciver, arriving without any contact with this culture, or perhaps simply with his character, has no such hang-ups, and his work therefore often comes like a breath of fresh air.

It could be said, though, that painting is a conservative act–and most of this new show is set in that medium. But it is because of this very conservative perception (and production) of painting that Maciver’s work is important, and interesting. It is often by utilising the most traditional of materials that the issues associated with that tradition can be most successfully addressed. Maciver’s work appears to be something like a critical attack on two directions painting seems to travel in, here: the serious painterly abstraction, and the overwrought figurative. Abstraction, of the AC4CA variety, is the more typically highly critically regarded, while community art prizes and centres that are filled with pictures of roses are extremely prevalent.

Crop Circles. 2016. Alex Maciver. Photo: Buratti Fine Art.

Crop circles is maybe the most emblematic of Maciver’s humour in addressing the typical figurative and abstract content of these painting styles. It is a simple scribbled spiral of paint, yet it declares itself a kind of landscape – but also a peculiar, kitsch, false landscape that is land art with a sense of humour – certainly no plains of arid, Australian soil. It is almost a leap too far to suggest that these spirals are anything other than scribbles of erased paint. Yet the simultaneous implication that this painting, by being a trivial scribble of paint, is not what its title claims it to be, but that what it claims to be is a crop-circle: one of those signs of false alien invasion, that pranksters and humourists makes, gives us the most accurate vision of the dynamic of Maciver’s work: as the creation of a mythos around false signs.

All through this exhibition he uses the paraphernalia of titling and painting to corrupt our understandings – on what could be understood as the lowest and basest of registers – but to great effect. No matter where we look, it seems as if Maciver is laughing at us. While we take his paintings seriously, or dismiss them for not being serious enough, they maintain a certain disregard for seriousness altogether. Their humour might be passed off as trivial, but it is in fact duplicitous. This character is what makes them important as art; that they render such stable ground as painting unstable and difficult to navigate.

It is also worth mentioning that it does not seem to be immediacy that informs his work, but flippancy. Unlike Cy Twombly, whose work Crop Circles reminded me of, there is something insulting about the rapidity and carelessness apparent in the work in this show. This work is unconcerned with the viewer’s desires, or at least wants to be perceived as not caring, whereas it also obviously cares deeply about showing up what we do desire; but it does not play into the wish for something incredible to be put on display. Sometimes the works are incredible anyway, but they do not exhibit the characteristics of trying to impress that defines much overwrought painting.

Roses. 2016. Alex Maciver. Photo: Burrati Fine Art.

There are also instances of excavation of cultural mores, something that seems related to his exhibition at Paper Mountain ‘I may live on as a ghost’ in 2013. Much of his abstraction evolves into a figurative form, corrupting the ‘purity’ of its form. Roses, a face, some trees, they appear out of the enamel, fluoro gloom of his abstract workings. The people that Maciver seems most comparable to in doing this are the more serious jokers of late twentieth century art – Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Their legacy is undervalued in our city, and their intelligence and wit, and willingness to make fun of the delusional mythic seriousness of the painter (particularly the abstract expressionists who came before them) is something worth learning from. (The current obsession with Gerhard Richter and Luc Tuymans is worth challenging on similar grounds). Maciver’s images are like half-remembered things, they rise incomplete, and our half-recognition of faces and roses and trees and people and a landscape all seem like the tropes of the pop-imagery of yesteryear. They are a use of the flotsam and jetsam of painting and abstraction. They are similar to the flippant devices of Maciver’s abstraction, but at work on the figurative, making basic, unrecognisable faces, stealing from colour-by-numbers books, and making ubiquitous palm trees silhouetted against a poison sky. All his scanned hand gestures downstairs seem related to this – the most typical and easily copied of gestures, indicative of a language, and in their copying, undoing it.

Maciver’s work raises the ire of many people, and it makes me happy that it does so. At the artist’s talks a painter said that he called his works ‘landscapes’ quite seriously, and Maciver, ever so polite, tried to indicate that his work, which he calls ‘landscapes’ in irony, was not an attack on him personally – though of course, we cannot deny that it is and was an attack. Hopefully some of the humour of Maciver’s work will slowly infiltrate or frustrate the continued machinations of our conservative, serious painting world.

by Graham Mathwin

2016: Issue 3: Shannon Lyons: A dead mouse and a broken coffee machine

A dead mouse and a broken coffee machine. 2016. Shannon Lyons. Photo: Dan McCabe

There is a scene in Mulholland Drive where a man in a diner, a ‘Twinkies’, tells the story of a dream he had about that very place. He has come to the diner where his dream was situated to dispel a consuming terror; caused by a man behind the restaurant. He and his friend go to the back of the diner to investigate. After approaching, slowly, with building terror at the understanding of his premonitive dream, he dies when the man turns out to be real, and to have appeared, looming out from behind a wall. Mulholland Drive repeats this framework several times, in different ways: you already know what is going to happen or it is in some way preordained, but when it does occur, it becomes somehow more incredible and estranging. In a twist, knowing what will happen leaves you powerless. In the most usually lauded scene, an actress (played by Naomi Watts) goes over her lines, playing out the terrible, cliché part that has been scripted for her. She then performs the lines again in her audition with an incredible change and sudden emphatic charge. The change between the two, the exact same lines performed twice, provokes a startling reconsideration of our expectations. Similarly when a singer drops dead on stage, and her emotionally stirring rendition of a song goes on as the recording it is, we are left estranged within Lynch’s manipulation of our emotions. In all of these cases, there is an element of doubling, between the dream and reality, the practice and the performance, the lip-sync and the recording, that is necessary to achieve the distinction between the expectation and the result. Perhaps the most pertinent description of this phenomenon is (oddly) given to us by Stephen King, who described the third and most potent kind of horror as terror, where you arrived home to find every object in your house replaced by an exact replica (and your friends with exact doubles – the Capgras delusion).

Lyon’s show is similarly a doubling, and also not what you might expect from its literal titling. The creeping doubts associated with a motionless, taxidermied mouse in a room that is no real café, but a parallel to the café next door, are quite insidious. The glowing white walls, the unlabelled coffee cups, and the small and very much once-real dead animal all provoke the sense of a nightmare. The script is as simple and short as it needs to be: the barista only tells the customer that the coffee machine is not working. It is worth noting that on the night of the performance, the barista was not an actor, but a barista. They answered the questions as themselves. Her only instruction was to tell everyone that the coffee machine was broken – this is also where the script ends, and she answered all other questions as best she could. The gallery space is not a perfect copy of the café next door, but it is a more perfect version of it. More pristine and clean, more uninhabited – except that everything within it is non-operational, defunct, or dead. Beside the functioning efficiency of MOANA coffee, MOANA gallery has become, in this show, a broken shadow – a nightmare version with an even more beautiful façade. The dead mouse is a small, sour nightmare, a subtle indictment of the situation of Moana: next door to a café that needs to maintain a certain façade. The dead mouse, belonging to the waste areas of cafes and city restaurants more than this façade, undoes our consumerist fantasies of sites of consumption; our obsessions with eating and drinking without consequence.

In Clarice Lispector’s The Passion according to G.H. the main character is driven to a crisis by the appearance of a cockroach while cleaning her maid’s quarters. This moment’s plummet into immanence and insanity seems strangely reciprocal to Lyon’s own small, abhorrent placement of a mouse in the pure white gallery space:

‘Meeting the face I had put inside the opening, right near my eyes, in the half-darkness, the fat cockroach had moved… It was just that discovering sudden life in the nakedness of the room had startled me as if I’d discovered that the dead room was in fact mighty. Everything there had dried up–but a cockroach remained… There, in the naked and parched room, the virulent drop: in the clean test-tube a drop of matter. I looked at the room with distrust. So there was a roach. Or roaches. Where? Behind the suitcases perhaps. One? Two? How many? Behind the motionless silence of the suitcases, perhaps a whole darkness of roaches–which all of a sudden reminded me what I’d discovered as a child when I lifted the mattress I slept on: The blackness of hundreds and hundreds of bedbugs, crowded together on atop the other… As in childhood, I then had the strong sense that I was entirely alone in a house, and that the house was high and floating in the air, and that the house had invisible roaches…’

It is particularly telling that this occurs in an otherwise spare and white interior ‘an insane asylum from which dangerous objects have been removed’, where G.H. is ‘trapped by the sun’ it is this kind of spiritual terror that is evoked by Lyon’s placement of the small, dead mouse beside the broken coffee machine in the too-bright gallery space, empty except for these strange elements. It is only a small horror, to place a dead mouse in a bright white room, but it is enough.

The work comes from the work of artists like Michael Asher, and despite their label of ‘institutional critique’; his interventions also often strike one as being more evocative than particularly critical. His collection of radiators from different parts of museums into one room seems to be a strange gathering and invocation of some sort, rather than being a criticism – or at least being equally as theatrical as it is critical. Yet Lyons has taken the process a step further. It no longer feels like the directly institutional engagement of Asher’s work, rather it warrants connection to Lynch and Lispector and their cinematic and literary devices and processes. Perhaps the inclusion of the script and a performer is to embrace the very theatrical nature of the work. It is interesting to see this work in relationship to the work Store she undertook with Paige Alderdice at Success earlier this year. That work had a similarly nightmarish aspect, a clean white room with a single window that looked out over another room filled with ceiling tiles in stacked piles, illuminated by dying, flickering fluorescents. The window in that work seemed more explicitly like a fourth wall. There is, in both works, the link to an institutional space’s history or present, yet also a complete theatrical transformation of that space.

Michael Fried notably criticised minimalism of being theatrical, and the term often has a negative connotation. Though this work still has something to do with the genre of ‘literalism’ that Fried disdained, it has moved beyond putting an audience in relation with its objecthood, or any sort of Judd like ‘specific’ objecthood, and we are witness to another kind of literalism–of illusion that takes place in the literal sphere. Other than this, it depends whether one thinks of theatre as the degeneration of art or not as to whether we agree with Fried. I am inclined to disagree; on the basis of his excessively essentialist thinking and supposition of theatre as something that is merely ‘glue’ between other (and it is implied “higher”) forms of art. The work is theatrical, and even though it is different from the minimalism that Fried spoke about, and a different (perhaps more ‘literal’) sort of theatre, it is certainly a good enough case to allay any concern that Fried might have been right in being dismissive of the literal and the theatrical.

Yet it is the nature of the double within this work that is particularly enticing and terrifying. Much like her near-imperceptible casting of blu-tack, or wall plugs in other exhibitions, Lyons is preoccupied with taking the paraphernalia of spaces and recreating them. In Francis Russel’s astute essay he states that ‘Against the notion that perception is both immediate and unmediated in character, Lyon’s work suggests that it is only through the reproduction and representation of things that we are able to approach a phenomenon’s sense.’ Yet this ‘sense’, to me, also does not make sense; much as Lispector’s G.H. becomes convinced of the immanence of things, and takes the squished matter of the cockroach in her mouth, so here there is something nightmarish and absurd. An inexplicable sensation comes over us, not only of the flow of commerce, the underpinning of the café, but its very façade-like nature. It is a sense that is like J.G. Ballard’s statement about his writing: that ‘the reality that you took for granted – the comfortable day-to-day life, school, the home where one lives, the familiar street and all the rest of it, the trips to the swimming pool and the cinema – was just a stage set. They could be dismantled overnight…Nothing is as secure as we like to think it is…A large part of my fiction tries to analyse what is going on around us, and whether we are much different people from the civilised human beings we imagine ourselves to be.’ Lyons is perhaps not as interested in defining a cultural epoch as Ballard (though there is definitely a case for it in focusing on the prevalence of cafes popping up around the city) but a similar sense pervades her construction of a parallel, a ‘stage-set’ to Moana coffee, a stage-set depicting a small nightmare.

All images: A dead mouse and a broken coffee machine. 2016. Shannon Lyons. Stainless steel, pine lining boards, commercial 2grp head coffee machine, coffee grinder, superwipe cloth, reclaimed jarrah, MDF, single wall paper takeaway coffee cups, coffee beans, coffee knocker, rubber mat, extension cord, plastic bin, bin liner, clipboards, glass, digital print on paper, IKEA ‘EKBY BJÄRNUM’ brackets, taxidermied mouse corpse and borrowed stanchions. Opening Night Barista: Sophie Johnstone. Photos: Dan McCabe.

by Graham Mathwin

2016: Issue 3: Artist’s Books: Wim Wenders: Places Strange and Quiet

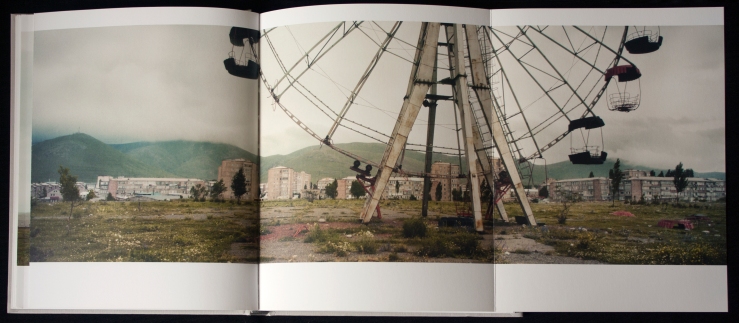

Ferris Wheel (Reverse Angle), Armenia, 2008. Wim Wenders. Places Strange and Quiet. Zeppelinstrasse: Hatje Cantz.

Highgate Continental, what used to be Apropos provisional, is Perth’s own Printed Matter: a bookstore and record store dedicated to photography and artist’s books and independent music releases. Artist’s books don’t have a huge market, but can be some of the most impressive things made in the book form. Though their relationship to coffee-table tomes sometimes weighs them down, there are frequently innovative and exciting works printed on paper and bound. After all, the book remains, despite its predicted death, one of the most potent articles of idea transmission–so why not transmit visual ideas as well as linguistic ones? It is a language that is both new and old–books have long been full of images, but did not have the recognition of a complete artistic creation, intended and considered, until the rise of conceptual art (earlier expressionist and constructivist (and futurist) books, and even comic books, existed before, but they were typically understood as illustration–though there are several notable earlier examples). Ed Ruscha, often cited as one of the most influential users of the form (Though it is worth questioning his originary status in art criticism, his legacy is undeniable), was precisely interested in the banality of mass reproducibility in the book form. Though the glamour of history is attached to his books now, his infamous 26 gas stations is a testament to the utter blandness of American highway driving and book printing. His later bookworks, 13 swimming pools and a broken glass and various small fires and milk, are stranger and more puzzling, but remain tied to, much like the rest of his practice, the sublime boredom of America’s desert utopia–Los Angeles. Ed Ruscha seems like an appropriate introduction as Wim Wenders, also a master of the very everyday subject matter, and American Highway driving, seems to call on Ruscha’s books for guidance. They are a similar format, with similarly undramatic choices in image placement. Wender’s work is also obsessed with the movement of people – in road movies, or his own travels – and the everyday spaces of his images seems to reciprocate with Ruscha’s investigations – particularly in 26 gas stations. Yet whereas Ruscha’s books were often self-referentially about their status as reproducible objects, whilst maintaining the aura of unfazed calm of the American dream, Wender’s book is traversed by the same issues that underpin his impressive filmography. The possibility of peace against war, the poetic pull of the estranged – and road movies. Wenders is a much more cosmopolitan and political artist of books than Ruscha, and the commercial and reproducible appeal of the books that attracted Ruscha, here gives way to their possibility of transferring and transporting us.

There is a telling similarity in both artists’ works however, in that their early and important contributions faded away or self-destructed in the critical sphere in their later life. Wenders later films are works of nostalgia, and so, in a way, is this book. It is a romance of the road, like many of his films, but mostly of a small-town America that has faded away. Wenders, it appears, has constructed an edifice of the retrospective rather than the progressive. The criticisms against Wenders also often centre on the apathetic characterisation and narratives of his work – some of which are needlessly romantic or boring. Wenders is not interested though, I suspect, in providing a narrative or drama. Paris, Texas goes out of its way to avoid or diffuse confrontations, even though the characters know they are meant to, at some point, do what they should, they go about it in circuitous ways that are more poetic and real than the typical kind of dramatization of human activity. This propensity to avoid conflict allows his work to pass by, often without offending people – some of whom probably need to be offended. Wenders himself claims that it is the desire among audiences to be cynical that resulted in the critical failure of some of his work. There can be little doubt that Wenders travels a relatively difficult path in trying to make movies in which there is very little conflict – and in some cases, as in Paris, Texas, a very clear attempt to avoid it. Everything about the film should lead to it being rather boring: a mute protagonist, long silences, landscape shots, but it is extremely successful despite all of this. In a similar way, Places strange and quiet is imbued with the majesty and also the banality that in combination make Paris, Texas so special. It is a globe-trotting book, with a similar emphasis on limited dialogue (though unlike many photo books, it does contain short epithets to its images), but it has at its heart the sense of a voyage, and seems like something of a road movie in book form.

Though his photographs, at their worst, occasionally resemble those of Stuart Klipper and other such panoramic photographers, Wenders often also imbues his more successful images with something that these photographers often fail to recognise: the human, mundane and political world that is as much a part of a landscape as its physical features. In particular, the presence of armed police, protestors, old warships that have been rendered into film sets, and bullet holes that riddle the walls of his birth country, Germany’s, capital, display a (still somewhat indistinct but none-the-less) political undertow to his work in photography. Wenders is not a photographer with a particularly strong political agenda (it is frequently overtaken by a mystical one), except perhaps as a pacifist, and his work is similarly not engaged in conflict, despite its willingness to address it – leaving the inclusion of the more violent matters ambiguous and uncertain. Wenders is not one for agonism or antagonism, he is, like the author/philosopher character in his extraordinary feature The Wings Of Desire, an advocate of peace. Yet perhaps his fondness for landscape over human subjects is not surprising.

Some of the most powerful of Wender’s images are of the radiation-affected zone around Fukushima nuclear power station. The film was affected by the radiation, and effectively destroyed, a sine wave moves over each grainy image he took of the site. There is the vague outline of a landscape beyond the surface of the film. The unintended results of the chemical process are fascinating, but also an ominous overlay. The destroyed images, of scenes that look perfectly neutral, by the strange wave of radiation, is a powerful reminder of things lying just below the threshold of perceptibility.

This book is also rather beautiful – though it is thankfully not filled with full-page spreads of landscape photos. It uses the aesthetic tropes of Wender’s films, with rich detail and flat horizons and stunning panoramic views. Yet there is also something that takes this book away from being another coffee table tome. It is, firstly, much more diminutive, more restrained. It secondly struggles with the possibility of peace against war, and the continued presence of violence and aggression in the world. Wender’s images are filled with an optimism that might be as misplaced as it sometimes appears in his films, yet that remains captivating for his belief in, and dedication to, it. Wender’s desire to construct an epic of peace is not done yet, and perhaps never will be done – but that is the nature of a narrative that has no victory, no conclusion. Wender’s explorations in photography look to the past, undoubtedly, but they are not the wholly conservative art one might expect because of this. Though they do not struggle, perhaps their unwillingness to fight against oppression and violence should not be mistaken for an unwillingness to address it nor undo its powerful hold. There is something tantalising about the possibilities Wenders presents in this tome, which infects us with his mystical hope.

by Graham Mathwin.

with thanks to Ian and Jack Wansbrough.

Comments

Post a Comment